ALULA: Anyone walking through the valleys and mountains of AlUla will notice its unique stone formations and untouched carvings — but not many would notice the echoes of falling rocks. Lebanese artist and electroacoustic composer Tarek Atoui says some of the valleys sound like “porcelain or crystal.”

“In Hegra, you don’t really hear it because it’s an archeological site,” he adds. “You really have to walk in valleys or in places that are wilder.”

Atoui has made a name for himself by blurring the boundaries of sound, technology, art, and collaborative performance. His latest participation — at AlUla Arts Festival, in Bayt Al Hams (The Whispering House) — is a testament to his ability to blend the human, the natural, and the machine. On the festival’s opening night on Jan. 16, Atoui, French musician Toma Gouband, and students from AlUla staged an intriguing performance using custom-designed instruments, natural objects such as tree branches and rocks, and cutting-edge techniques.

Tarek Atoui and French musician Toma Gouband during their performance at AlUla Arts Festival on Jan 16. (Supplied)

“I believe sound can take you to places where you really speak about the inner and not just the surface — and that’s what I love about it,” Atoui tells Arab News. “Sound is an abstract medium, so it can create sensations and emotions in us in an unexpected way, and what you choose to do with it is very personal and intimate. It’s something that allows you to speak of an identity, of an intimacy, of a fragility, that maybe image doesn’t allow you to.

“If you want to find out about a place then, of course, you find out about its history, archeology, geology, its different social and political realities. But it’s mainly about talking to the people that inhabit it. And the best way, in my case, to have a dialog with people is through what I do. So that’s why it was very important to reach out to people in this way.”

Bayt Al Hams, a dedicated hub for Atoui’s work, is a soundscape that will be changing almost seasonally, he explains. It showcases a selection of works that rely largely on four natural elements: water, stone, metal, and glass.

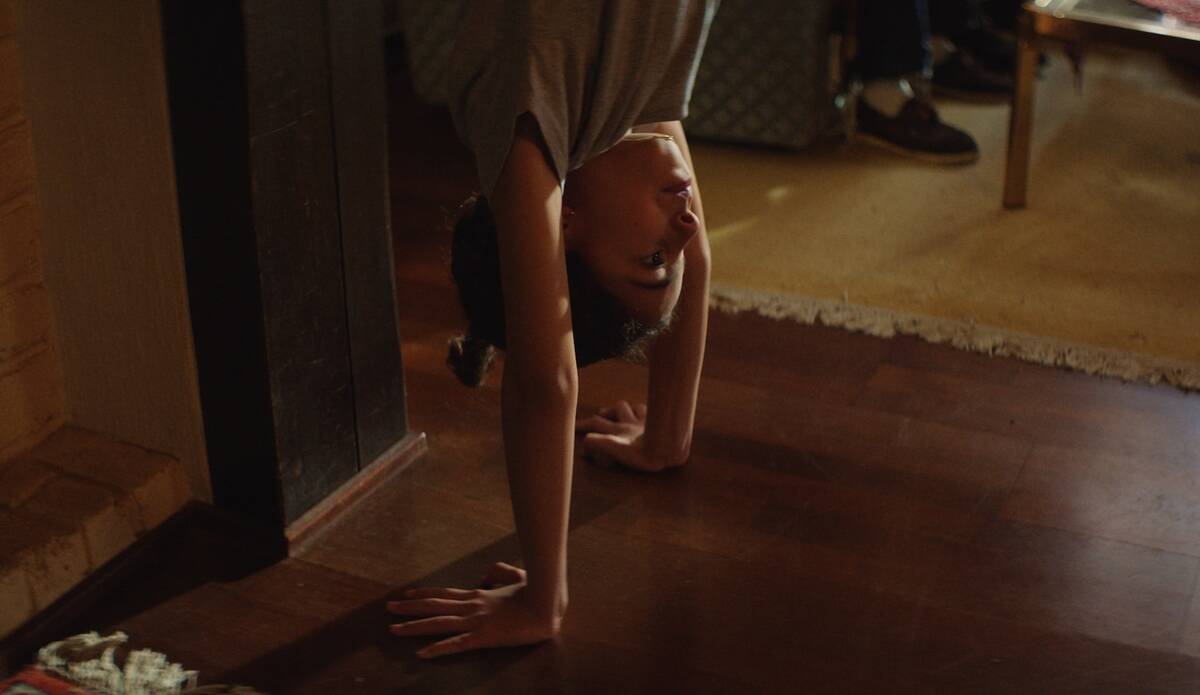

Visitors to Atoui's “Bayt Al-Hams” exhibition. (Supplied)

The interactive space is scattered with contraptions that create sound, from textile squares to tablas to metal-infused ink hooked up to machinery developed by Atoui himself.

“It’s a kind of easy way to get into a complex, deep topic,” he says. “The things that are here have a double life. Let’s say they’re animated and automated through computer software and algorithms I write, which kind of drive this space, but they are also brought to life by human beings, the students we work with, the musicians we work with,” he explains.

Atoui was first inspired by techno music, or, as he describes it, “music that had physicality to it.” He went on to study contemporary music, and began to understand that any sound can be musical. “You can work with sound in so many ways to make music. And that was liberating for me, because I didn’t know how to compose with scores and classical instruments,” he says.

He was interested in poetry, literature, and theater too, but when he went to France — where he is now based — for university, he fell in love with the crossover between art, mathematics, abstraction, and sound.

His unique art, he says, came “through a lot of improvisation, like thinking how to use the computer as a music instrument, learning how to code and to program and to create software for sound, and, from there, learning how to work with electronics and build electronic instruments.”

Atoui’s latest participation — at AlUla Arts Festival, in Bayt Al Hams (The Whispering House) — is a testament to his ability to blend the human, the natural, and the machine. (Supplied)

He was also interested in education, which began manifesting in his practice.

“Not having a musical background myself, I wanted to encourage people from different realms to also have a say in sound, or to use new technologies to make sound and music,” he explains.

He’s worked with Palestinian refugees in camps, with groups in the suburban areas of Cairo, and in parts of Europe, Asia, and the US.

“It was a really mind-opening experience to travel to all these places and to perform, teach, and interact with people. Slowly, I started to slide towards the art world, because this is where I found (more) freedom. I didn’t feel I was exclusively a musician,” he says.

Atoui is not concerned that his work may be too avant-garde to ever go mainstream.

“That’s no problem at all,” he says. “We each have our sensibilities and tastes. To me, also, there are musical things that are not music.”