LONDON: More than half of Syria’s population faces food insecurity as the country grapples with the aftermath of 13 years of civil war, the abrupt collapse of Bashar Assad’s regime, and a surge of returnees.

Inadequate funding for aid organizations during this political transition risks deepening and prolonging the crisis.

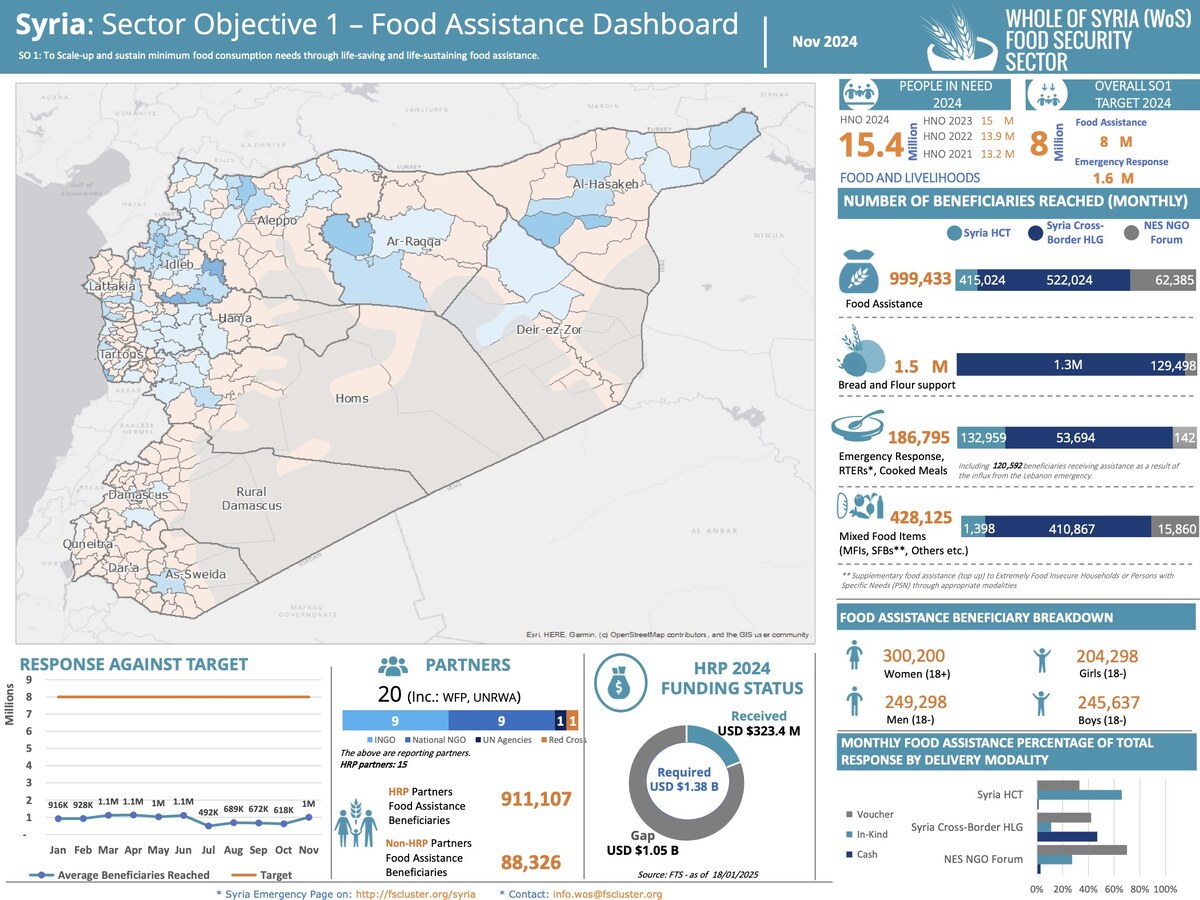

A recent report by the Food Security Cluster, a UN-led coordination group, revealed that 14.5 million people in Syria are food insecure, including 9.1 million facing acute food insecurity and 5.4 million at risk of hunger.

The report, published on Jan. 25, emphasized that Syria’s sudden power shift and ongoing political transition have increased pressure on its fragile food systems, reshaping humanitarian needs.

Rola Dashti, executive secretary of the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, described the current phase in Syria as a “critical juncture,” stressing that the country must either move toward reconstruction and reconciliation or risk falling into deeper chaos.

“The stakes for the country, and for the region, could not be higher,” she said in a January statement.

“Food insecurity is rampant, healthcare systems are crumbling, and entire communities have been uprooted. This is one of the world’s most protracted humanitarian crises, and our findings make clear it could get worse if immediate steps are not taken.”

A boy carries freshly-baked bread as people line up outside a bakery in the Syrian capital Damascus on December 21, 2024. (AFP)

On Dec. 8, a coalition of opposition groups led by Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham seized control of Syria’s capital Damascus, following a sweeping 12-day offensive that toppled Assad.

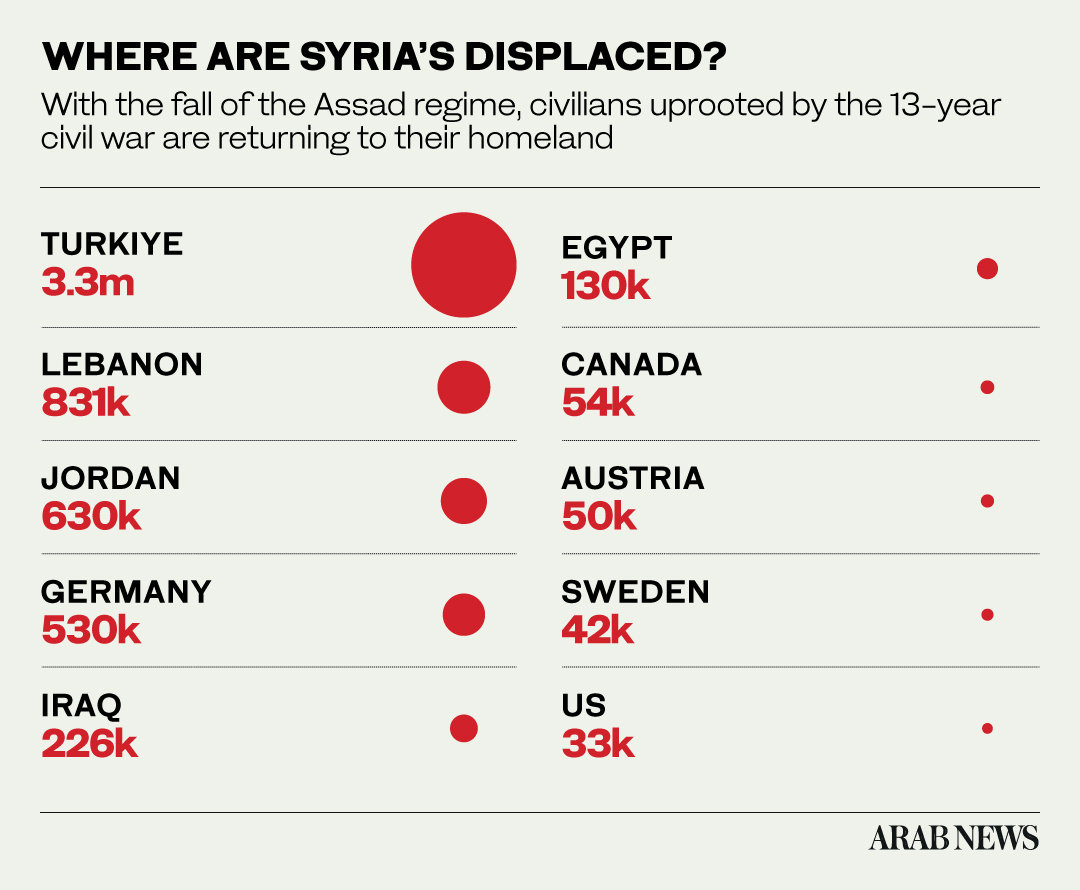

And although Assad’s ouster provided some relief to Syrians, it also plunged the country into fresh political and economic uncertainty, with the country deeply fractured and up to 1 million refugees expected to return by June, according to UN figures.

Recent clashes have sparked a new wave of displacement, with some 1.1 million people newly displaced, mainly in Idlib, Aleppo, Homs, and Hama.

The surge in violence since late November has been a major driver of food insecurity, according to the Food Security Cluster’s report. Warehouses and public services have been looted, while damage to agricultural infrastructure has disrupted the planting season.

Syria’s political transition post-Assad has fueled the hunger crisis, leaving millions in urgent need of aid. (AFP file)

This lawlessness, especially in northeastern and southern Syria, has created logistical challenges, blocked roads, and restricted aid access, severely disrupting food security.

Some 90 percent of Syrians currently live below the poverty line and some 16.7 million need humanitarian assistance, according to the UN.

Without bold reforms and swift international support, these needs are expected to grow, ESCWA warns.

The Food Security Cluster said $560 million is needed to fund a three-month emergency response providing food assistance and livelihood support during Syria’s political transition and uncertainty.

However, funding for aid remains insufficient. Cindy McCain, director of the World Food Programme, has said that some governments are reluctant to increase support for urgent humanitarian needs in Syria under the country’s new interim rulers.

And although the new leadership in Damascus has pledged a radical overhaul of the struggling economy, including privatization and public sector job cuts, it faces enormous challenges.

Western sanctions and more than a decade of conflict have left Syria’s economy in tatters. The country’s gross domestic product has contracted by 64 percent since the beginning of the war in 2011, according to a recent ESCWA report.

The report, released in late January, noted that Syria’s currency lost nearly two-thirds of its value against the US dollar in 2023 alone, driving consumer inflation to an estimated 40.2 percent in 2024.

Syria’s currency lost nearly two-thirds of its value against the US dollar in 2023 alone, driving consumer inflation to an estimated 40.2 percent in 2024. (AFP)

Joshua Landis, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, believes the collapse of the Assad regime is largely tied to the failure of Syria’s economy.

“Government pay for officers in the army was $30 a month, and only $10 for enlisted men, which gives one a sense of the terrible need,” he told Arab News.

“The HTS government has increased those government wages by 400 percent, thanks to the largesse of Qatar, but wages remain extremely low.”

In mid-December, Syria’s interim government announced plans to dramatically increase the salaries of public servants. However, this plan involves laying off a third of the state workforce, Reuters reported.

The first wave of layoffs came just weeks after Assad’s ouster. Ministers in the interim government told Reuters that removing “ghost employees” — those who received salaries for doing little or nothing — was part of a crackdown on waste and corruption.

Syria’s interim government announced plans to dramatically increase the salaries of public servants. but the plan involves laying off a third of the state workforce. (AFP)

Landis says the layoffs are likely to worsen the hunger crisis for certain groups.

“Employees of the old regime are quickly being purged, as new employees whose ambitions and loyalties are better aligned with the new government are recruited by HTS,” he said.

“This means that hunger and insecurity is being redistributed to those Syrians who used to be favored by the Assad regime.”

Residents of Damascus and its hinterlands say that while the capital has seen an influx of foreign goods and a drop in prices since Assad’s departure, purchasing power remains low, especially as public servants and many private sector workers have not been paid in two months.

“We have a saying in Syria: a camel costs only one pound, but we don’t have that pound,” Umm Samir, a 55-year-old housekeeper from Al-Hajar Al-Aswad, Rif Dimashq, told Arab News.

“Prices of food have certainly dropped, and there are no shortages,” she said. “But in our area, many have not brought a pound home for almost two months.”

She added: “For example, a bottle of olive oil cost 100,000 Syrian pounds before Dec. 8; now it’s sold for 75,000. A kilogram of sugar was 20,000; now it’s 9,000.”

Blacksmiths work in a forge in the town of Douma, on the outskirts of the Syrian capital Damascus. (AFP)

The drop in prices is partly due to a strengthening of the Syrian pound against the US dollar. On Friday, the dollar traded at 9,900 Syrian pounds, down from about 15,000 Syrian pounds before Dec. 8.

Syria expert Landis noted that while “food prices went down a bit once HTS took Damascus, because Turkish and foreign goods began to move freely into Syria without tariffs, bread prices went up.”

He added: “Bread is a major part of the Syrian diet, particularly for the 50 percent of Syrians facing food insecurity.”

Damascus residents told Arab News that a bundle of subsidized bread, which once cost 500 Syrian pounds, has seen its price jump to 4,000 Syrian pounds following Assad’s fall from power.

Syrians stand in queue to buy bread in the town of Binnish in Syria's northwestern province of Idlib. (AFP file)

When many cannot afford this essential food item, the influx of Turkish and Western goods — much more expensive than local products — makes little difference. If anything, it serves as a stark reminder of the struggle many families face to meet their basic needs.

Yusra, a 33-year-old computer engineer from Muhajreen, an upscale neighborhood in central Damascus, said that although three members of her household of six are breadwinners, they still could not afford many food items, such as meat, fruit, and sweets.

“It doesn’t matter that we now have Snickers bars, Ulker cookies, or brie cheese in local supermarkets when most people can’t afford basic things like sugar or apples,” she told Arab News.

“In my family, whenever we have an occasion, be it a birthday or Eid, we have to cut corners to buy cake or meat.

Syrians work at a vegetables market in Aleppo, on December 23, 2024. Aleppo's old city. (AFP)

“My brother works for a private marketing company but has not received his salary for January as the business is struggling.”

But the problem goes beyond families’ inability to meet basic needs. WFP chief McCain called Syria’s hunger crisis a national and regional security issue, particularly during this critical transition period.

“What’s at stake here is not just hunger — and hunger is big enough. But it’s about the future of this country and how it moves forward into this next phase,” she told the Associated Press during her first visit to Syria in mid-January.

On the national level, Syria expert Landis warns that if the interim government led by President Ahmad Al-Sharaa fails to implement economic and political reforms, it will likely face growing opposition.

Syria's de facto leader Ahmed al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Mohammed al-Golani, speaks to the media during a meeting with Qatar's Minister of State Mohammed bin Abdulaziz Al-Khulaifi, after the ousting of Syria's Bashar al-Assad, in Damascus, Syria, December 23, 2024. (REUTERS)

“Syrians are expecting the new government to jump start the economy, get the US and Western governments to lift sanctions, and to unite the country once again, which will mean that Syria’s oil and gas wells will once again be used by the Damascus government and not the Qamishli government,” he said, referring to the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.

“It should be remembered that before 2011, oil and gas revenue provided 50 percent of the government budget. If President Al-Sharaa cannot get the economy back on its feet quickly, he is likely to face growing opposition and Syria is likely to remain turbulent and unstable.”

Farmers work to harvest wheat at a field in Raqa, northeastern Syria, on May 23, 2024. (AFP)

Since early December, protests have erupted across the country, with demands ranging from justice for disappeared activists to calls for improved public services and greater representation for various Syrian sects.

On the regional level, “a poor and hungry Syria will continue to pump out refugees,” Landis said. “All of Syria’s neighbors are counting on Syrian stability and economic growth to entice refugees to return home.”

He added: “If Syria stumbles, the reverberations will be felt throughout the region. The country will remain divided among foreign militaries and a battleground that could easily destabilize its neighbors.”

Caption

The UN warns that unless Syria achieves a stable transition, the hunger crisis will worsen, and reliance on aid will persist. The transition must establish inclusive governance, credible transitional justice, and stronger institutions to build public trust, according to ESCWA’s January report.

The report also states that the country’s stability and recovery depend on regional and international support, including sanctions relief and economic cooperation.

Without political and economic reforms in collaboration with regional and international partners, ESCWA believes Syria risks prolonged instability, further fragmentation, and becoming a haven for cross-border crime.