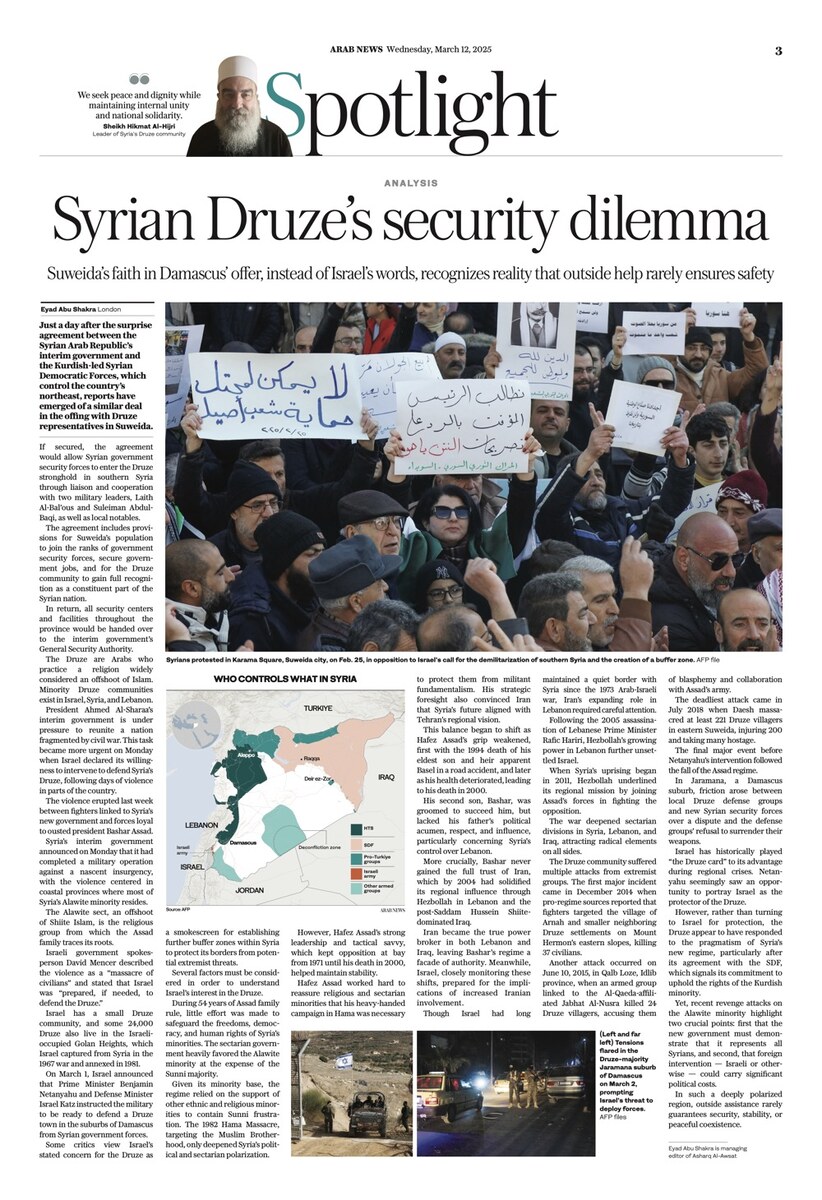

LONDON: Just a day after the surprise agreement between the Syrian Arab Republic’s interim government and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which control the country’s northeast, reports have emerged of a similar deal in the offing with Druze representatives in Suweida.

If secured, the agreement would allow Syrian government security forces to enter the Druze stronghold in southern Syria through liaison and cooperation with two military leaders, Laith Al-Bal’ous and Suleiman Abdul-Baqi, as well as local notables.

The agreement includes provisions for Suweida’s population to join the ranks of government security forces, secure government jobs, and for the Druze community to gain full recognition as a constituent part of the Syrian nation. In return, all security centers and facilities throughout the province would be handed over to the interim government’s General Security Authority.

The Druze are Arabs who practice a religion widely considered an offshoot of Islam. Minority Druze communities exist in Israel, Syria, and Lebanon.

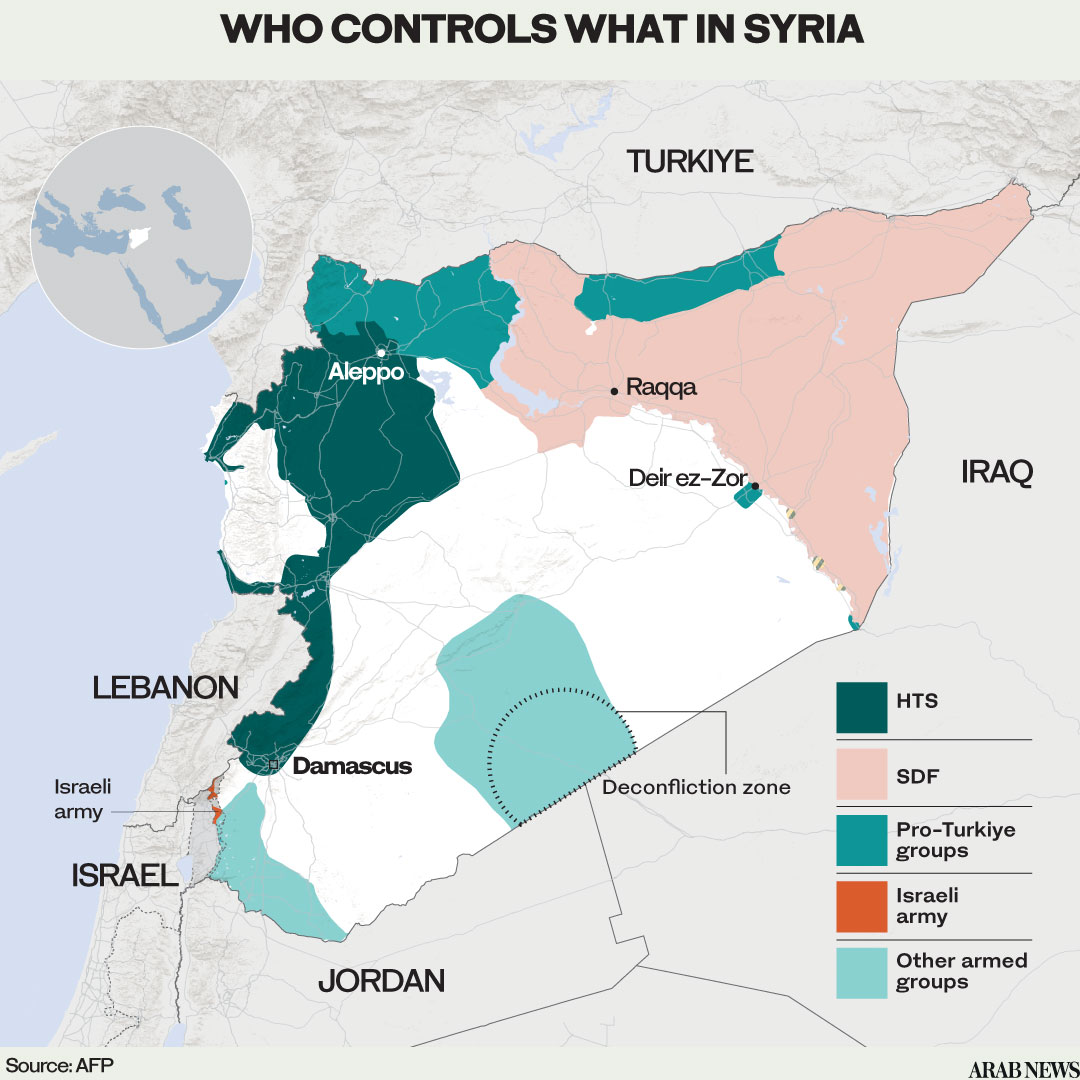

President Ahmed Al-Sharaa’s interim government is under pressure to reunite a nation fragmented since the onset of civil war in 2011. This task became even more urgent on Monday when Israel declared its willingness to intervene to defend Syria’s Druze, following days of violence in parts of the country.

The violence erupted last week between fighters linked to Syria’s new government and forces loyal to ousted president Bashar Assad.

Syria’s interim government announced on Monday that it had completed a military operation against a nascent insurgency, with the violence centered in coastal provinces where most of Syria’s Alawite minority resides.

The Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiite Islam, is the religious group from which the Assad family traces its roots.

Israeli government spokesperson David Mencer described the violence as a “massacre of civilians” and stated that Israel was “prepared, if needed, to defend the Druze,” though he did not provide details on how this would be carried out.

Israel has a small Druze community, and some 24,000 Druze also live in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, which Israel captured from Syria in the 1967 war and annexed in 1981.

On March 1, Israel announced that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Israel Katz had instructed the military to be ready to defend a Druze town in the suburbs of Damascus from Syrian government forces.

Some critics view Israel’s stated concern for the Druze as a smokescreen for establishing further buffer zones within Syria to protect its borders from potential extremist threats.

Syria’s fluid political situation has always had regional repercussions. As one of the most strategically important countries in the Near East, Syria’s internal dynamics inevitably affect its neighbors.

Netanyahu’s recent statement that Tel Aviv was committed “to protecting the Druze community in southern Syria” did not surprise observers who have closely followed Syrian affairs since the 2011 uprising.

Several factors must be considered in order to understand Israel’s interest in the Druze.

During 54 years of Assad family rule, little effort was made to safeguard the freedoms, democracy, and human rights of Syria’s minorities. The sectarian governance and police state they established heavily favored the Alawite minority at the expense of the Sunni majority, which makes up more than 75 percent of Syria’s population.

Given its minority base, the regime relied on the support of other ethnic and religious minorities to contain Sunni frustration. The 1982 Hama Massacre, targeting the Muslim Brotherhood, only intensified animosity, heightened distrust, and deepened Syria’s political and sectarian polarization.

However, Hafez Assad’s strong leadership and tactical savvy, which kept opposition at bay from 1971 until his death in 2000, helped maintain stability.

Hafez Assad worked hard to reassure religious and sectarian minorities that his heavy-handed campaign in Hama was necessary to protect them from militant fundamentalism. His strategic foresight also convinced Iran, his trusted ally since the Iran-Iraq war, that Syria’s future aligned with Tehran’s regional vision, reducing the need for Iranian over-involvement.

This balance began to shift as Hafez Assad’s grip weakened, first with the 1994 death of his eldest son and heir apparent Basel in a road accident, and later as his health deteriorated, leading to his death in 2000.

His second son, Bashar, a medical doctor, was groomed to succeed him, but lacked his father’s political acumen, respect, and influence.

Many of Hafez Assad’s veteran political and military lieutenants were sidelined, as were key policies and alliances, particularly concerning Syria’s control over Lebanon.

More crucially, Bashar never gained the full trust of Iran, which by 2004 had solidified its regional influence through Hezbollah in Lebanon and the post-Saddam Hussein Shiite-dominated Iraq.

Iran became the true power broker in both Lebanon and Iraq, leaving Bashar’s regime a facade of authority. Meanwhile, Israel, closely monitoring these shifts, prepared for the implications of increased Iranian involvement.

Though Israel had long maintained a quiet border with Syria since the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Iran’s expanding role in Lebanon required careful attention.

While Israel did not fear a direct Iranian military threat, given Tehran’s strategic realism and reluctance to attack America’s key regional ally, Iran’s persistent influence and nuclear ambitions remained a source of concern.

Following the 2005 assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, Hezbollah’s growing power in Lebanon, and its grip on the country’s southern border, further unsettled Israel.

When Syria’s uprising began in 2011, Hezbollah underlined its regional mission by joining Assad’s forces in fighting the opposition, alongside pro-Iran Iraqi, Afghan, and Pakistani Shiite militias.

The Syrian conflict quickly became one of the region’s bloodiest wars, killing hundreds of thousands, displacing millions, and devastating cities and villages.

The war deepened sectarian divisions in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, attracting radical elements on all sides.

The Druze community suffered multiple attacks from extremist groups. The first major incident came in December 2014 when pro-regime sources reported that fighters targeted the village of Arnah and smaller neighboring Druze settlements on Mount Hermon’s eastern slopes, killing 37 civilians.

Another attack occurred on June 10, 2015, in Qalb Loze, Idlib province, when an armed group linked to the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat Al-Nusra killed 24 Druze villagers, accusing them of blasphemy and collaboration with Assad’s army.

The deadliest attack came in July 2018 when Daesh massacred at least 221 Druze villagers in eastern Suweida, injuring 200 and taking many hostage.

The final major event before Netanyahu’s intervention followed the fall of the Assad regime.

In Jaramana, a Damascus suburb, friction arose between local Druze defense groups and new Syrian security forces over a dispute and the defense groups’ refusal to surrender their weapons.

This added to the army’s challenges in maintaining control over the Alawite heartlands in Latakia and Tartous and the Kurdish-held northeast.

Israel has historically played “the Druze card” to its advantage during regional crises. Netanyahu seemingly saw an opportunity to portray Israel as the protector of the Druze, mirroring Iran’s role as the “guardian of the Shiites” and certain Western governments’ historical ties to Christendom.

However, rather than turning to Israel for protection, the Druze appear to have responded to the pragmatism of Syria’s new regime, particularly after its agreement with the SDF, which signals its commitment to uphold the rights of the Kurdish minority.

Yet, recent revenge attacks on the Alawite minority highlight two crucial points: first that the new government must demonstrate that it represents all Syrians, and second, that foreign intervention — Israeli or otherwise — could carry significant political costs.

In such a deeply polarized region, outside assistance rarely guarantees security, stability, or peaceful coexistence.