DUBAI: Lebanese artist Lana Khayat is currently staging her first solo show in Saudi Arabia. “The White Lilies of Marrakech: Women as Timeless Narratives” runs at Riyadh’s Hafez Gallery until March 25, and is, according to the press release, an homage to the titular city’s Jardin Majorelle, which celebrates its centenary this year, “as well as Lana’s enduring narrative on the strength and resilience of women.”

Khayat says the exhibition also marks a significant step forward in her work, which blends influences from nature with abstraction and calligraphy.

“In this show, you will see a bolder look, a more confident me,” she tells Arab News. “Nature was always my main inspiration, but recently I’ve added another layer of botanical forms into my work, which will be seen for the first time in this show. An obvious example is the lily. The lily is an intrinsic part of my work; it was always present. But now it is taking center stage, so it becomes more apparent. The lily, which is the symbol of women… in my earlier works, it was very shy, but in my most recent work, you can see the lily taking the foreground — big and lush, and very present. I’m very shy. I’m a big introvert, but I’ve learned that, actually, the truer I am to my work, the more people relate to it. I think women are very strong, and their strength is very silent, but at the same time very commanding — and I definitely feel more confident in my work.

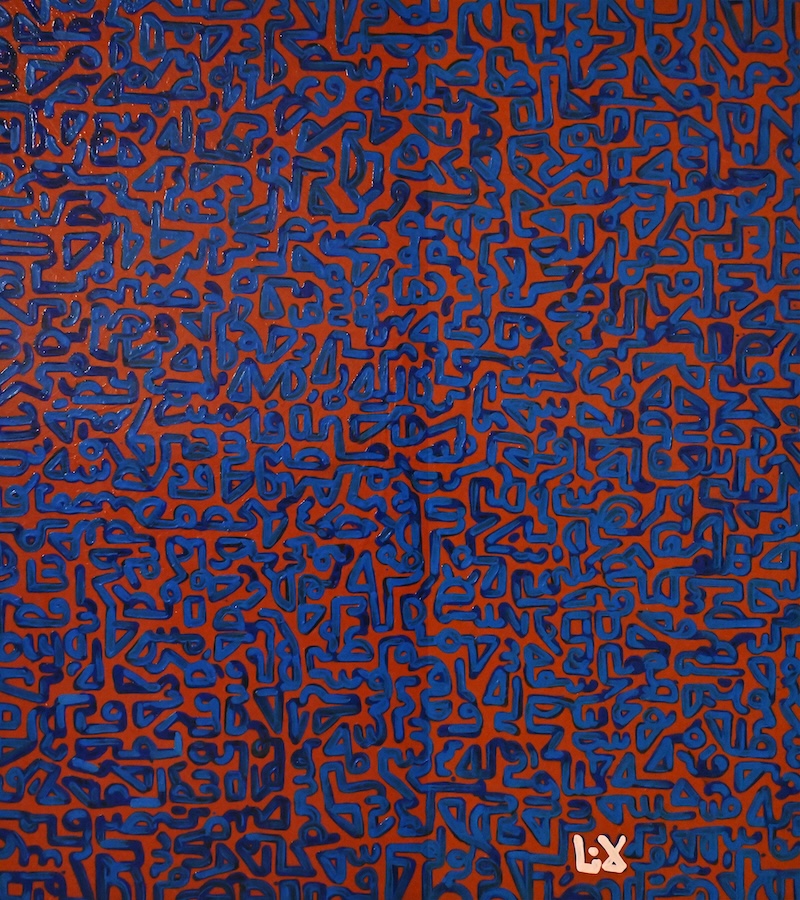

'Echoes of Ephemeral Whispers.' (Supplied)

“I even changed my signature,” she continues. “It has become more bold.”

The inspiration for the exhibition, as the name suggests, came when Khayat was visiting Marrakech.

“Marrakesh is a historical cultural crossroads; it embodies the fusion of tradition and modernity, which is essential to my work,” she says. “Its Berber and Arab and Andalusian influences make it the perfect backdrop to my work. And the theme of the show was born of out of my fascination with how women’s stories persist throughout time — through language, through culture, through nature. The lilies, for me, are women, standing strong. They’re there. They flourish. Lilies are among the strongest plants and flowers, and water lilies are present in the Jardin Majorelle. So it’s this interplay of my study of women, my study of lilies, and my study of languages, and I felt that Marrakesh is the perfect place to carry all of these meanings.”

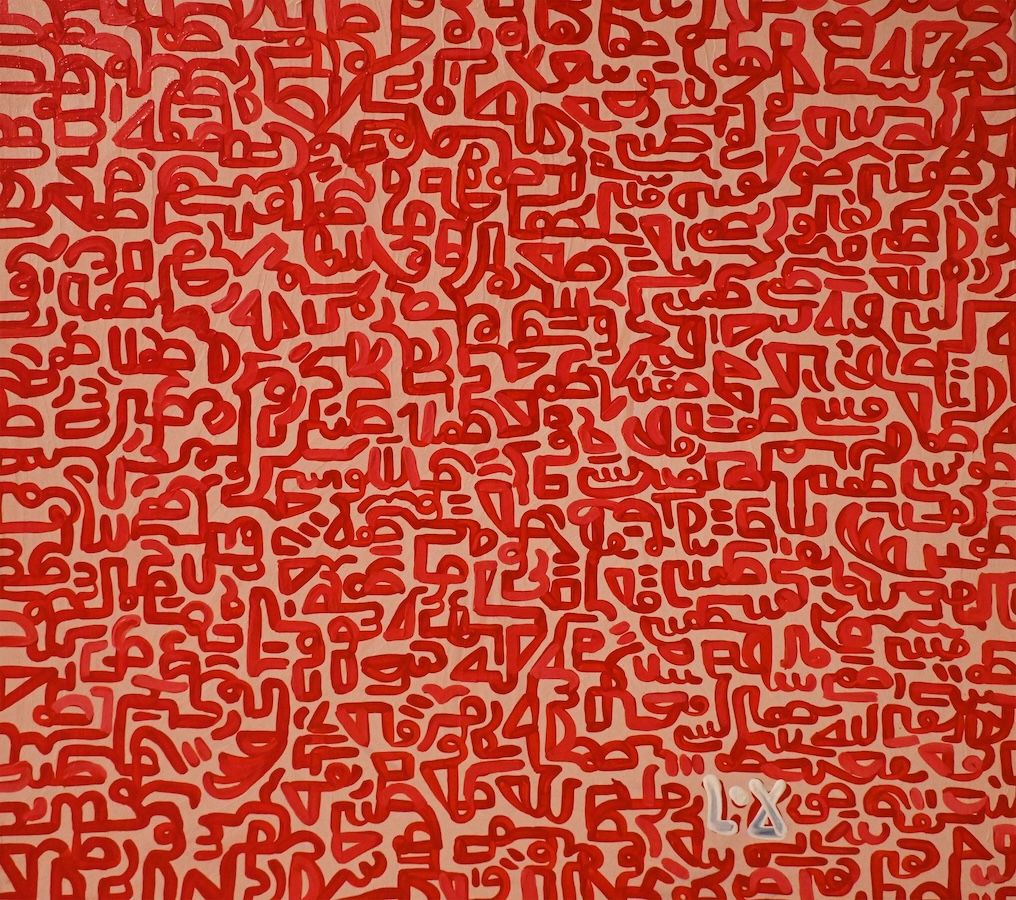

'The Vermilion Lilies of Marrakech.' (Supplied)

Given her ancestry, it’s no surprise that Khayat became an artist. Her great grandfather, Mohamad Suleiman Khayat, was a famed restorer of lavish Syrian-style Ajami rooms whose work is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among other prestigious establishments. His son and grandson — Khayat’s father — followed in his footsteps.

“I was raised with this,” says Khayat. “From them, I learned patience. But it was male-dominated, so I had to forge a place for myself in this artistic lineage, which wasn’t easy, but I slowly found my voice.”

A large part of discovering that voice was moving to New York from Lebanon after completing her degree in design. “I remember in my childhood I was copying Van Gogh, you know? Vases and flowers… I had images of that in my head,” she says. “But after I was in New York, and I spent some time working at the Guggenheim, and then when I moved to Dubai, that’s when I actually had a bit of an internal struggle. ‘Should I keep (my art) to myself, or should I just show it and see where it will take me?’ And after some internal conflicts between me and myself, I thought, ‘There’s actually nothing to lose. Let’s just see where it takes me.’ And around 10 years ago, I was lucky to meet Qaswra (Hafez), the founder of Hafez gallery, who really believed in my work and supported it.”

'Between Bloom and Form.' (Supplied)

She loves Monet’s work, she says, but her main inspirations were other female artists — though not necessarily because of their art.

“It was more the artist’s journey and how they fought for that rather than the art itself,” she says. “For example, I love Frida Kahlo for her boldness.” A few days after our interview, she writes to add that Lebanese artist Etel Adnan’s work is also an inspiration, because “her fearless blending of disciplines — of poetry, landscape, and abstraction — encourages my own pursuit of art that honors resilience, transformation, and the enduring strength of women.”

In her twenties, Khayat was more influenced by Western art, “but now I appreciate Arab art more and more,” she says. “My work has multiple layers. It’s both personal and universal. It’s a celebration of my Arab heritage. Also, I use language in a very meditative way — the script I use, it’s a carrier of tradition and a testament to history. My work is also very abstract. The script I use dissolves into gestures and the nature that I’m inspired by morphs into fluid shapes. You know, Arab culture is vast and diverse, but in my work, I try to reinterpret it and show how it evolves; it’s not stagnant.”

Calligraphy is, she says, “a quiet dialogue between me and the painting, between the audience and the painting, and it’s open to interpretation. I would love for the viewer just to lose themselves in the painting and find the meaning where they want. And it’s a dialog also with history, because, as I said, I would like to reinterpret Arab heritage and show how it’s evolving.”

That last point is one of the things she most hopes audiences will take away from the Riyadh show. “I hope it feels intimate and universal for them, and I hope they see it as a celebration of script. I hope they see the abstraction I make in my work as an evolution of Arab heritage and I hope they see how, for me, nature is a witness to history,” she says. “And I hope they enjoy it.”